Introduction and definition

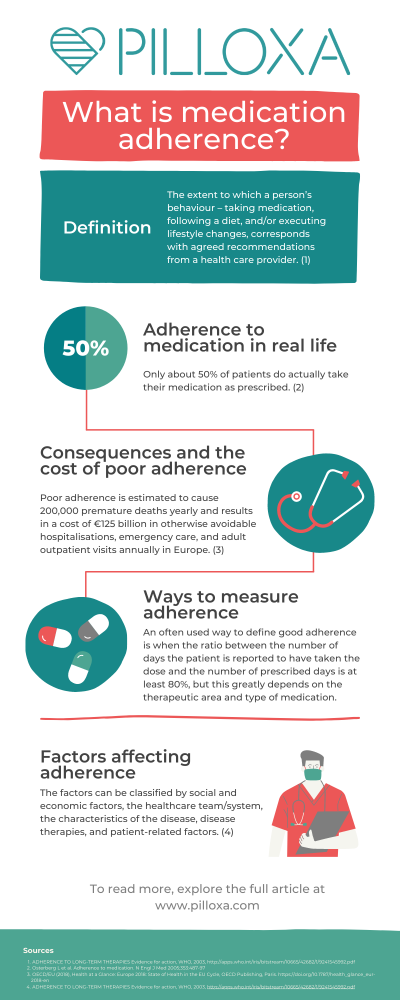

Adherence to medication is a term used to describe how well patients take their medication according to the plan created together with their healthcare professional. Sometimes it also includes adherence to other medical advice such as attending physical care, diet and lifestyle interventions, etc. The word adherence has come to replace the word compliance since it better captures the active rather than passive role of the patient. Several authors have tried to nail down a definition of adherence and the World Health Organization’s definition from 2003 is one of the most commonly used, defining it as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider” (1). It’s important to note that even though adherence describes a behavior occurring over time, the term persistence is used when referring to adherence over a long period of time.

In this article, we will explore how adherence is measured, what adherence means in the context of real life, factors influencing adherence, a few adherence solutions that are already available, and what the cost of poor adherence is to society as a whole.

What is “good” adherence and how is it measured?

What is good, moderate or poor adherence?

The fact that there is no universally well established definition of good, moderate or poor adherence makes the assessment of adherence and comparison between study results complicated. An often used definition of good adherence is when it is reported that a patient has taken their dose(s) correctly at least 80% of the prescribed days. Sometimes medicine possession ratio (MPR), the number of days the medicine is in the patient’s possession (collected from pharmacy), is used instead since this can more easily be tracked in registries. Again – 80% is often used as the threshold, however one should keep in mind that this threshold is arbitrary and does not directly relate to clinical relevance.

Direct methods

Direct methods to measure adherence include measuring the concentration of metabolites of the drug itself or the molecules added (markers) to the medicine solely for this purpose. Measures are usually made in blood, urine, feces, saliva or breath tests. This way to measure adherence is probably the most accurate. However, it has been hard to find a perfect marker to add to the drug for these kinds of measurements since absorbance and clearance patterns would have to be identical among subjects and not affected by diet, lifestyle, genetics, etc.

White coat adherence has also been described, i.e patients become more adherent and hence reach higher concentrations just before a doctor’s visits. Other disadvantages are the intrusive nature of taking the tests, the cost, the effect this testing has on the treatment alliance between the caregiver and patient, and that it is not practical in large scale, everyday treatment. Another direct method is direct observed treatment, DOT, where healthcare personnel or family members confirm the ingestion of a dose. These measures have been used in psychiatric settings and also in tuberculosis medicine in rural areas. A modern approach to this is the AI-confirmed ingestion, which solutions such as AI-cure utilize.

Subjective measures

Earlier, often used methods have been to let patients or care providers submit how medicine has been taken, for example, in paper or electronic diary form or in self estimation questionnaires. Several scales for this have been developed such as Morisky, BMQ and Hill-Bone. Unfortunately, subjective measures have many times been proven not to correlate very well with actual medicine intake but has been described as one of the least intrusive methods.

Objective measures

Pill count is probably the most used traditional method. Pills are then counted at a given moment, for example at the end of a study. This is compared to the number of pills the patient received from the start minus expected number of doses taken and the discrepancy indicates the level of nonadherence. This gives an idea of doses taken but of course there is no guarantee that the pills have actually been ingested or taken at correct dose times.

Secondary database analysis, for example analysis of refilled prescriptions compared to prescribed days as mentioned above, is sometimes used.

Electronic Medication Packaging (EMP) devices have been more commonly used and are by some considered the golden standard since the 1990’s. They often include a combination of features such as: (i) recorded dosing events and stored records of adherence; (ii) audiovisual reminders to signal time for the next dose; (iii) digital displays; (iv) real-time monitoring; and (v) feedback on adherence performance. The advantages of these devices are that they provide data about when the doses have been taken and that more work is needed to intentionally trick the device. Disadvantages are that it is often more costly, refilling needs to be addressed in some way, and some patients consider the box too chunky so they take out pills and store in other ways leading to false classification as non adherent (2).

A recent solution involves a sensor inserted in pills that is activated when ingested and thus delivers data about actual ingestion. This approach is of course harder to trick and it provides more accurate data. Drawbacks are the cost, the intrusiveness of the method, and usability since the user must wear a patch on their belly at all times.

Adherence to medication in real life

Chronic disease and health care spendings

Life expectancy is steadily increasing (3) and chronic disease is rising with it. In the EU, 100 million people living with chronic diseases medicate daily (4) and in the US 6 out of 10 adults have one chronic condition and 4 out of 10 have 2 or more (5). In 2017, countries in Europe spent on average 9.6% of GDP on health care, corresponding to an average spending of €2773 per person and the biggest spenders exceeded €4000 per person. On average, medicines accounted for 17% of total health expenditure (excluding medicines used in hospitals). In the US, 90% of the $ 3.5 trillion annual national health care expenditure was spent on people with chronic conditions and mental health conditions (6,7).

Adherence differences in populations

With this background, it is evident that a substantial part of the population is medicating on a daily basis and that astronomical resources are being spent on this. However, only about 50% of patients do actually take their medication as prescribed (8). Trials suggest that adherence levels vary between groups: for example adherence to antihypertensive medicine is ranging between 20-80 % (9,10). A primary nonadherence (meaning not filling the initial prescription) of 6-44% in asthma therapy has been demonstrated and secondary adherence has varied widely between 5-77%. Adherence to antidepressants also seems to differ greatly and 20-80% of patients have been reported not to follow prescription (11).

Even where therapies are more directly linked to saving lives, for example, after transplantation, poor adherence is reported among 20-50% of patients (12,13). Contrary to common beliefs, not only the elderly take medicine, there is a large group of younger people (aged 65 and below) with chronic diseases that medicate on a daily basis (14). Among them, nonadherence is a frequent problem, and some studies show that this group accounts for more missed doses than the older group (15,16,17,1,8,19,20).

Consequences and the cost of poor adherence

For the individual, poor adherence might have fatal consequences. It might, for example result in the loss of a transplanted organ or lead to stroke. Nonadherence to preventive cardiovascular medication increases the risk of hospitalization by 10-40% and the risk of mortality by 50-80% (21). Some studies suggest that up to 30% of people who seek emergency care is due to medical related problems (22) and an often cited number is that 10% of hospital enrollments are directly due to poor adherence (23). Poor adherence also causes worry among relatives, increases care utilization, and drives costs. In the US, nonadherence costs between $100-300 billion every year in healthcare costs alone (24). In Europe, poor adherence is estimated to cause 200,000 premature deaths yearly and results in a cost of €125 billion in otherwise avoidable hospitalisations, emergency care, and adult outpatient visits (25).

Factors affecting adherence

Traditionally, nonadherence has been viewed as something that is strictly related to the patient but over the last decades several factors have been identified as contributing to poor adherence. In 2003, WHO chose to divide these factors into: social and economic factors, the healthcare team/system, the characteristics of the disease, disease therapies and patient-related factors (26).

WHO states that “Patient characteristics have been the focus of numerous investigations of adherence. However, age, sex, education, occupation, income, marital status, race, religion, ethnic background, and urban versus rural living have not been definitely associated with adherence. Similarly, the search for the stable personality traits of a typical nonadherent patient has been futile – there is no one pattern of patient characteristics predictive of nonadherence.”

In recent years, focus has in some degree shifted back to individual forgetfulness and this has been acknowledged to account for a big part of the unintentional nonadherence (27,28). Pilloxa has explored the most common causes for medication nonadherence in our article here.

Adherence solutions

Several different approaches have been tried in order to tackle the widespread problem of poor adherence over the years. Often educational and informational interventions have been tried as well as individual and family therapy. Other approaches have been to simplify treatment regimens, to lower the cost for medicine, and to simplify the management of medication (e.g. pill organizers). For treatment monitoring, pill count has long been the golden standard whilst electronic monitoring has also become more frequent in recent years as technology has made it possible (29). Furthermore, reminders have gone from analog alarm clock reminders to be more advanced such as SMS text messages and calls.

In recent years, interest has increased in eHealth and mHealth (electronic and mobile health) and new solutions such as eMMD (electronic multi-compartment medication devices) and apps (mobile applications) have explored the opportunities within these fields. It seems that these newer electronic approaches have to some extent replaced old methods and are by some considered the new golden standard (ibid).

However, the clinical evidence that interventions do actually improve adherence and/or health outcomes vary in different studies. When it comes to analog pill organizers, studies show that these might increase adherence and outcome when used in some groups but results are inconclusive (30,31). Among older patients there was large room for improvement of usability factors in these devices (32), and possibly this lack of usability could in some groups lead to risks such as incorrect medication taking.

One large Cochrane review 2006 concluded: “For short-term drug treatments, counseling, written information and personal phone calls helped. For long-term treatments, no simple intervention, and only some complex ones, led to improvements in health outcomes. They included combinations of more convenient care, information, counseling, reminders, self-monitoring, reinforcement, family therapy, psychological therapy, crisis intervention, manual telephone follow-up, and other forms of additional supervision or attention. Even with the most effective methods for long term treatments, improvements in drug use or health were not large” (33). However, none of the reviewed studies included only an electronic monitor and reminder system.

A following Cochrane review in 2014 concluded: “…Across the body of evidence, effects were inconsistent from study to study, and only a minority of lowest risk of bias RCTs [randomized controlled trials] improved both adherence and clinical outcomes. Current methods of improving medication adherence for chronic health problems are mostly complex and not very effective, so that the full benefits of treatment cannot be realized…”. This review mostly included studies using informational/educational or therapeutic approaches (34).

Later reviews draw the conclusion that interventions, especially those including behavioural aspects and prompts to take medication, have an effect on adherence but that the effect on health outcome is unclear (35,36). Furthermore, there are some reviews that conclude that electronic reminders do have an effect on adherence (37) and two reviews show effect of electronic reminder systems on increased adherence indicating that this might be the new and possibly most promising kind of intervention to improve adherence (38,39).

We will most likely see a mix of analog, hardware, and software solutions as well as different strategies on tackling the issue at hand depending on the therapeutic area. It is great to have a variety of options to choose from since each patient population is different and requires tailored support to their unique needs. The end goal is to support patients in living better lives by improving adherence.

Conclusion and discussion

Poor adherence and how it relates to poor health outcomes and increasing cost of care has been known for a long time. It is evident that there lies a great opportunity to use health care budgets more efficiently if a solution to poor adherence can be found and implemented. It is rather surprising that a problem of this magnitude is still not addressed in a satisfying way in routine care.

Numbers of adherence rates are to be found in research but very few initiatives seem to be implemented to measure and track adherence rates in clinical practice. In some areas where concentration of drugs are being measured, for example within transplantation care, there is still no golden standard for improving adherence. Already in 2009 in the Nonadherence Consensus Conference Summary Report, this need was identified when one stated “the group also recommended that adherence monitoring be incorporated into the routine clinical management of all organ Tx recipients. Most importantly, it is imperative that such activity be reimbursed”(40).

Reasons for this might be the lack of direct financial incentives through reimbursement but also that there has been a challenge to find solutions that measure and address non-adherence in a correct way while also being acceptable from a user perspective, not too complex and intrusive and also cost effective.

It is clear that every person’s adherence pattern is a result of complex and highly individual underlying factors. It therefore seems reasonable that solutions aiming at improving adherence must be adapted and flexible around the individual behavior, disease, treatment, and other factors. Hopefully new technology with the capacity to analyze large amounts of data, and to create individually tailored responses, will be a gamechanger in patient support.

I believe that it is time to consider the end users not as “patients” but to acknowledge the fact that most of us will medicate for a chronic condition and that taking a pill a day does not change our priorities in life. Working, taking care of our loved ones, and engaging in activities will be taking up our time. Most of us do not want to spend more time than necessary on medicine rituals. Thus, for an intervention to be accepted it will need to flow seamlessly into our lives, providing more benefit than hassle. Complexity in the background but simple to the user seems to be a winning concept.

After decades of crushed hopes to see a widespread adoption of adherence solutions, maybe the COVID-19 pandemic will be the catalyst that finally drives this transformation in the medical space. It has accentuated the need for solutions to both facilitate and monitor adherence in home environments. New solutions are presented to the market at a rapid pace and it will be interesting to follow this development. Finally we also see a will to change reimbursement models that can fuel this change.

A very interesting question is, who will be the leaders driving this transition? Will it be healthcare providers and payers? New healthtech players? Or pharmaceutical companies seeking the opportunity to sell adherence as a service, e.g. in pay for performance models? It is clear that there is a massive opportunity for anyone who solves this problem in an efficient way and there is a risk of losing competitiveness for those that don’t and most likely we will see more and more collaborations between these actors.

– Helena Rönnqvist, CEO of Pilloxa

About Pilloxa

Pilloxa is a technological, regulatory, and legal platform for pharma to create dynamic apps to support patients and learn from user data. We provide innovators with the tools and insights to enable sustained learning within health so that our customers can focus on patient needs and how to best support them. Agile and affordable, pricing starts at €2500 a month and it takes only one month to launch a branded patient app with us.

Download

Our infographic below gives a great quick summary over the topic of medication adherence, download here.

Sources

- ADHERENCE TO LONG-TERM THERAPIES Evidence for action, WHO, 2003, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf

- Lam WY, Fresco P. Medication Adherence Measures: An Overview. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:217047. doi:10.1155/2015/217047

- WHO, Global Health Observatory (GHO) data https://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/en/

- Chronic disease alliance: A unified prevention approach. http://www.alliancechronicdiseases.org/fileadmin/user_upload/policy_papers/ECDA_White_Paper_on_Chronic_Disease.pdf

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, About Chronic Diseases, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2017 Highlights, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf

- Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp.; 2017, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/tools/TL200/TL221/RAND_TL221.pdf

- Osterberg L et al. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487-97

- Costa FV. Compliance with antihypertensive treatment. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;18(3-4):463-472

- Cramer JA, Benedict A, Muszbek N, Keskinaslan A, Khan ZM. The significance of compliance and persistence in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(1):76-87

- ADHERENCE TO LONG-TERM THERAPIES Evidence for action, WHO, 2003, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf

- Lennerling, A. & Forsberg, A. Self-reported non-adherence and beliefs about medication in a Swedish kidney transplant population. Open Nurs. J. 6, 41–6 (2012).

- Denhaerynck, K. et al. Prevalence, consequences, and determinants of nonadherence in adult renal transplant patients: A literature review. Transpl. Int. 18, 1121–1133 (2005).

- http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/lakemedel

- Henriksson J. et al. A Prospective Randomized Trial on the Effect of Using an Electronic Monitoring Drug Dispensing Device to Improve Adherence and Compliance, Transplantation. 2016 Jan;100(1):203-9.

- Butow P. et al. Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. JCO November 10, 2010 vol. 28no. 32 4800-4809

- F. Dobbels et al. Adherence to the immunosuppressive regimen in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review, Pediatric Transplantation, Volume 14, Issue 5, pages 603–613, August 2010.

- Age-related medication adherence in patients with chronic heart failure: A systematic literature review., Kreuger et al., Int J Cardiol. 2015 Apr 1;184:728-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.042. Epub 2015 Mar 4.

- The impact of age and gender on adherence to antidepressants: a 4-year population-based cohort study, Amir Krivoy et al., Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015 Sep;232(18):3385-90. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3988-9. Epub 2015 Jun 21.

- Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse, Charles H. Hinkin et al., AIDS. 2004 Jan 1; 18(Suppl 1): S19–S25.

- Ho PM et al, Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2009; 119(23):3028-3035

- Fryckstedt J. et al. Läkemedelsrelaterade problem vanliga på medicinakuten, LÄKARTIDNINGEN, 2008-03-18 nummer 12

- Iuga, A. O., & McGuire, M. J. (2014). Adherence and health care costs. Risk management and healthcare policy, 7, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S19801

- Thinking Outside the Pillbox: A System-wide Approach to Improving Patient Medication Adherence for Chronic Disease. A NEHI Research Brief – August 2009, https://www.nehi.net/writable/publication_files/file/pa_issue_brief_final.pdf

- OECD/EU (2018), Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en

- ADHERENCE TO LONG-TERM THERAPIES Evidence for action, WHO, 2003, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf

- Konstadina Griva, Ph.D., Andrew Davenport, FDRC, Michael Harrison, FDRC, Stanton P. Newman, Ph.D.Non-adherence to Immunosuppressive Medications in Kidney Transplantation: Intent Vs. Forgetfulness and Clinical Markers of Medication Intake 2012, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, Volume 44, Issue 1, August 2012, Pages 85–93, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-012-9359-4

- Khan MU, Shah S, Hameed T. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence among hypertensive patients attended National Health Service Hospital, Sunderland. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6(2):104‐108. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.129175

- Haberer JE1, Robbins GK, Ybarra M, Monk A, Ragland K, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Bangsberg DR.Real-time electronic adherence monitoring is feasible, comparable to unannounced pill counts, and acceptable. AIDS Behav. 2012 Feb;16(2):375-82. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9933-y.

- Watson SJ, Aldus CF, Bond C, Bhattacharya D.Systematic review of the health and societal effects of medication organisation devices.BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul 6;16:202. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1446-y. Review.

- McGraw C. Multi-compartment medication devices and patient compliance.Br J Community Nurs. 2004 Jul;9(7):285-90. Review.

- Adams R, May H, Swift L, Bhattacharya D. Do older patients find multi-compartment medication devices easy to use and which are the easiest? Age Ageing. 2013 Nov;42(6):715-20. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft113. Epub 2013 Aug 26.

- Haynes RB1, Yao X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, McDonald HP. Interventions to enhance medication adherence.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Oct 19;(4):CD000011.

- Nieuwlaat R1, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, Agoritsas T, Mistry N, Iorio A, Jack S, Sivaramalingam B, Iserman E, Mustafa RA, Jedraszewski D, Cotoi C, Haynes RB. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 20;(11):CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4.

- Conn VS1, Ruppar TM2, Enriquez M2, Cooper P2. Medication adherence interventions that target subjects with adherence problems: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016 Mar-Apr;12(2):218-46. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.06.001. Epub 2015 Jun 15.

- Conn VS1, Ruppar TM2. Medication adherence outcomes of 771 intervention trials: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2017 Jun;99:269-276. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.008. Epub 2017 Mar 16.

- Vervloet M1, Linn AJ, van Weert JC, de Bakker DH, Bouvy ML, van Dijk L. The effectiveness of interventions using electronic reminders to improve adherence to chronic medication: a systematic review of the literature.Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000748 696-704 First published online: 1 September 2012

- Paterson M, Kinnear M, Bond C, McKinstry B. A systematic review of electronic multi-compartment medication devices with reminder systems for improving adherence to self-administered medications. Int J Pharm Pract. 2017 Jun;25(3):185-194. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12242. Epub 2016 Feb 1. Review.

- van Heuckelum M1, van den Ende CHM1,2, Houterman AEJ3, Heemskerk CPM4, van Dulmen S5,6,7, van den Bemt BJF1,3, The effect of electronic monitoring feedback on medication adherence and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017 Oct 9;12(10):e0185453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185453. eCollection 2017.

- R.N Fine, Becker et al, Nonadherence Consensus Conference Summary Report DO – 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02495.x American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons